Economic Analysis on Gacha Game Pricing - Part 3 - The Pricing of Gacha Games

Written by Researcher Alex and Edited by Rei Caldombra 12/1/25 Previous Part: Economic Analysis on Gacha Game Pricing - Part 2 - Innovation, Supply, and Demand — Blog Under a Log

In this article, I will explain how companies who use a free-to-play model will use different monetization strategies to get money out of consumers. This applies to video game companies who made games that are for almost everyone to maximize the chances that everyone will purchase the game while lowering the cost of the video game to $0 so everyone can afford the game. Certain strategies like selling chances to obtain a product or having lower price points are optimal for gaining the maximum amount of money out of consumers.

Free-to-play games cannot sell their game above $0, so they resort to selling virtual items in games to recuperate costs and to gain profit. There are two types of monetization strategies that video game companies can take. The first way is to sell the item at a fixed price like selling a virtual popular shirt for $10. The second way is to sell the chance of being able to get the item such as selling $1 lottery tickets that have a 1-100 chance to give a virtual popular shirt if you win.

Fixed Sale Price System

Let’s first examine what happens when a game company sells a digital product at a fixed price. Depending on what is being sold, such as new DLCs, seasonal cosmetics, new game-enhancing content in a game that have fixed priced products that introduce content that is unique to the game will appeal to a range of consumers to have an increased incentive to pay for the new content product within the game. Unique content can be released together to make the elasticity more vertical. In other words, the digital product is content which can be unique or similar to content in other video games. Video game companies can decide how unique or similar this digital product can be when sold to consumers.

It is also important to know if the consumer can pay for the product. Within the fixed price product market, there are three highlighted consumers in the market that can be identified based on the economic definitions.

The first category is the non-spenders of the product who will not spend any money on the game. This is commonly called a free-rider in economic terms or in game terms a free-to-play player. Since they will not spend any money on the game, they will not spend any money on the presented fixed price product. They are considered ultimate savers in economic terms and will almost always use their disposable income on other things beside the game.

The second consumer is the minnow or low spender individual which will play for a specific unique content in the game. This is a saver that is willing to spend frugally to maintain their disposable income and will pay for what they specifically want. They will have different amounts of disposable income that they are willing to spend on the price of a product, but this demand is fixed by the fixed price of the product and only a certain amount of saving individuals that are willing and have enough money to pay for the price of the product will actually buy the product. This consumer type is elastic from their willingness to spend a limited budget of disposable income to buy a single desired product which other games with similar products could have at cheaper prices.

The third consumer is the person who is willing to spend money on the product and has the capacity to buy the product. They will likely consider almost any presented product highly unique and will buy the product within their large financial capacity. These are whales (in gacha terms) or spenders in economic terms. However, they are considered savers who accumulate a lot of money within their own budget (for total budget for disposable and essential spending) that will aggressively spend more on their favorite content, brand, or game when given disposable income. There are varying types of spenders which some will spend a random amount of money but will only spend the amount of money associated with the fixed cost and will not spend above the maximum disposable income amount that they have on hand. This consumer type is inelastic because they are willing and able to spend as much as they want on their desired product with their high amounts of disposable income and the consumer can likely additionally afford spending the same budget amount in other games with similar products that may be more expensive than the desired product in the game that is being played by the consumer.

These three consumers can be graphed onto a chart to show their willingness to purchase a virtual item at a fixed price in a video game. The “Price US Dollars” axis represents how much a person is willing to pay for a desired product in a game. The “Quantity” axis represents how many consumers have a copy of the game. In short, each consumer has a copy of the game and an amount of disposable income willing to be spent on a desired product in the game. Consumers are buying a desired product which is a product that is an idea that the consumer desires in the game. Please note that measurement in these charts represents a single moment in time which prevents consumers from shifting between different types over time.

In this fixed sale, consumers above the price of the product line will think the product is cheap relative to the disposable income they are willing to pay for the product. While consumers that are unable to buy the product will consider the product to be too expensive relative to their willingness or ability to pay for the product. The ability of the consumer to be able to buy the product or not represents a binary choice for spending money.

When the two lines from a wealthy consumer (spender) and a saving consumer (saver) meet, there is a sharp curve which changes from the spender to the saver and vice versa. This is to represent the binary choice between wealthy dedicated fans and consumers who are hindered by economic and choice factors. This is to account for logic that the consumer is “maybe interested to purchase” or “maybe financially able to purchase” accounts for a not purchased product. In other words, pondering whether to buy the product means that the product is not purchased, thus representing a binary choice to purchase a product.

This fixed method is notably inefficient with claiming additional revenue above the priced product. Remaining disposable income mostly from consumers who thought the fixed price product is still cheap and who are willing to spend more for the product is not accounted for or obtained by the seller of the fixed priced product. This is especially noted by the large amount of money that the spender or whales are still willing to spend above the price point of the fixed priced product. To get this remaining disposable income, the fixed concept must become variable or adjustable in nature. This is the chance system found in gacha games, slot machines, possibility games, and gambling systems.

Chance sale price system

Now what if the price of the desired digital product could be adjusted for each and every consumer in order to maximize giving their disposable income to the video game company? In this context, the price should be a range rather than a fixed price. For a company to make both the spender consumer and saver consumer willing to spend their money, the product should be priced in a range rather than a point. However, simply saying that a wealthy consumer should spend $10 for a product and an average consumer only needs to spend $5 for the same product would be unequal pricing for the wealthy consumer. Although this may seem unfair to the wealthy consumer, there is an economic loophole in this method. The wealthy consumer would just simply adjust their disposable income to become an average consumer, thus only spending $5 instead of the $10 price point for a wealthy consumer. The video game company cannot force how much a consumer wants to spend, only by enticing willingness of the consumer to spend. Notice that spender consumers and saver consumers are all savers, thus being able to save up disposable income to spend. These consumers that can decide their price for the product would very likely choose the cheaper option for the same item from a saving economic standpoint.

Therefore, the product should not be a product with a fixed price but rather a chance. Giving the digital product to be purchased via chance removes the price value that is visible to the consumer. Instead of $5 for a virtual popular shirt, it is a 5% chance (5 out of 100) to get a virtual popular shirt. Removing the price tag removes the price visible to the consumer, thus redirecting their judgement to how much a 5% chance is for purchase. Now the real question is how much should a chance be priced for a consumer?

Pricing a chance sale

Ideally to get the maximum amount of income out of all consumers, video game companies should price their products at the maximum amount that a consumer is willing to spend or at the equal to the disposable income of the highest spending consumer. Note that this is the price of a digital product and not the price of a chance. In short, video game companies want all consumers to spend all of their disposable income so they expand their consumer base and raise their price range to the consumer that has the most disposable income to get the highest spending consumer. This can be represented in the chance sale graph.

Since all consumers who get a chance have an equal weight of getting the product, the consumer who can spend more of their disposable income can buy multiple chances to get multiple chances to get a product. In short, the more disposable income you have, the more chances you can purchase. Which gives the player more opportunities or chances to get the desired product. A person who buys one chance can either fail or win, but a person who buys two chances and loses the first time has another chance to either fail or win. This is the basic concept of a variable product for a chance sale which can also be called a variable priced product. Now lets apply this concept to the saver and spender consumer types.

The consumer who is a saver will have a tolerance for spending a limited amount of money to try to obtain the variable product. This is similar to how people are willing to spend a certain amount of money to buy a lottery ticket for a small chance to win a prize. There is also a possibility that the saver will get the variable product due to chance.

Spenders or whales will be willing to spend a certain amount of money to greatly increase the chances of them obtaining the product. In doing so, they may get their digital product early with their increased quantity of purchased chances. This is why they may not spend the maximum full price of the product because of the quantity increase towards the chance that they may obtain the product due to the spender having more attempts to obtain the product. However, having more attempts to obtain the product will cause the spender to spend more money. Therefore, a company will be incentivized to make the variable priced product to have a minimal chance to obtain the product to increase the amount of attempts bought by consumers.

In the chance sale graph, it is logically not ideal to set the price as a chance of the digital product to be above the consumer with the disposable income. In other words, if a chance is abysmally too low, wealthy consumers may not obtain the product no matter how many chances that they can purchase. If I am the wealthiest consumer and each chance is $1, I should be guaranteed to get a desired digital product that guarantees me a win 1 out of 100 chances played if I have $100. If I have horrible luck and win on my 100th try, then the price of the digital product is $100.

But if I try to get the product and only have $90, then the product is considered unobtainable and obtainable to me if I am the wealthiest consumer. If I am the wealthiest consumer and don’t get the product, then the product is priced too high (1 out of 100 chances) for any other consumer to obtain. Being a consumer that is buying multiple chances means that you are trying to make a chance system to become guaranteed for you to get the desired digital product. In short, consumers are buying out risk by purchasing multiple chances and directly purchasing the product.

Therefore, it is important for the company to set a limit for the maximum price of the product because any price point which gives the consumer the product that is above the consumer's maximum disposable income gives the product the chance of being unobtainable that is outside of the agency of the consumer. This affects the people who are spenders that will spend to maximize the guarantee that they will obtain the product or to buy the product at its full price. This is why a limit for the maximum price is the actual price of the digital product or the ideal sum of chances to obtain the digital product.

Since the price of the digital product is established by the chance rates (1 out of 100 rolls and you will get the product), it is important to establish the price of each chance (how much is each roll?) to know the true value of the product. This is important to know if there is an optimal way to price a chance.

Price of each chance

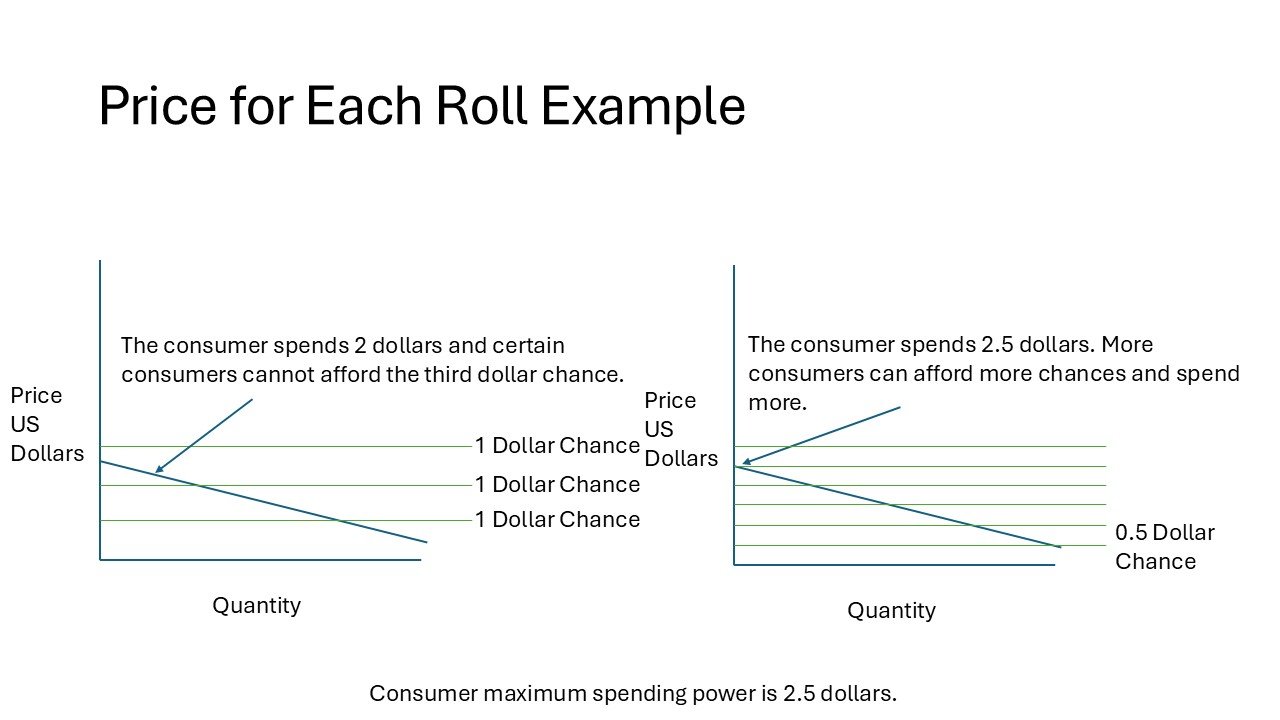

It is important to distinguish that the actual product sold is the “chance to obtain the desired digital product” rather than the digital product. Whether or not the digital product is sold becomes separated by this intermediatory product of chance (money or digital currency 🡪ticket to get product🡪actual digital product vs. money or digital currency🡪actual digital product). Therefore, pricing the chance is a key component of selling a digital product in a chance sale. This can be demonstrated with two simple graphs of a digital product where rolls are chances that a consumer can purchase. In the two graphs showing the price for each roll, the “Price US Dollars” axis is how much the consumer is willing to spend on the digital product while the “Quantity” axis represents how many consumers have a copy of the game. In this example, let's say the consumer owns 1 copy of the game and has $2.5 of disposable income which is at the leftmost side of any of the graphs. The left graph is divided by $1 chances while the right graph is divided by $0.5 chances.

When looking at these graphs, the left graph shows that the consumer cannot afford to buy a 3rd chance which would cost $3. Since the consumer only has $2.5, $0.5 would not be enough to buy a 3rd chance or roll. The company would not get $0.5 and loses out on potential money. However in the right graph, the rolls all cost $0.5 which the consumer can spend $2.5 to get 5 rolls. The company would get all of the disposable income with no remainder balance left for the consumer. Overall, this means that a smaller price per chance is more beneficial to the company by allowing the consumer to spend more of their disposable income to get the product while also being beneficial to the consumer by giving the consumer more chances or rolls to use to get the product.

Therefore, the price per each roll or chance should be at a minimum derivative or at the smallest amount available to be purchased by the consumer. This is to reduce the remainder of disposable income left over by the consumer after each chance purchase which is less than the price of one chance. A consumer cannot buy a chance if there is not enough money held by the consumer to buy it. Ideally, the sum price of total rolls should exactly match the consumer maximum disposable income. If a consumer has $10 but each roll is $6, then the consumer will only spend for 1 roll and have $4 remaining. $4 will not be spent towards the game product. But if a consumer has $10 and each roll is $2, then the consumer will spend 5 rolls and have $0 remaining. $10 will be spent towards the game product. It is also ideal to have the roll spent at the full amount. For instance, if a consumer has $10 and each roll is $10, then the consumer will only spend for 1 roll and have $0 remaining. $10 will be spent towards the game product.

However, since not everyone has a similar maximum amount of disposable income, the full price version of $10 per roll would alienate consumers who have less or more than $10 in their disposable income budget. One consumer could have $9 while another consumer has only $11. Therefore, pricing the roll at $1 per roll would allow any consumer to spend all of their disposable income with no remaining leftover cash that is insufficient for purchasing a single roll.

More rolls equals more company control

The incentive of pricing each chance as low as possible also allows the consumer to buy more chances. Although this benefits the consumer by giving more opportunities to roll for a chance to win their desired product, companies can use this to their advantage by using the law of large numbers to get a desired probability chance to occur. The application of having more rolls indicates that the chance average will become more consistent over time. If a 50/50 chance coin is flipped multiple times such as 100 times, then the probability for total heads and tails will reach around 50% frequency for either side vs a smaller number of tries such as 1 time, 2 times, or 3 times. This follows the law of large numbers in statistics. Therefore, having more rolls that have smaller odds will increase the chance that the smaller odds will appear. Gacha games or chance systems are incentivized to give tiny percentage chances because they are made to have more rolls to capture the maximum amount of disposable income. Gacha games or chance systems want to capture the maximum amount of disposable income that a consumer has. Therefore, they will increase the amount of rolls at a low price point per chance. This increase in more rolls allows for the game owner or company to gain the option to increase the chance that a desired probability will occur after multiple rolls. In simple terms, game companies can achieve a target probability by lowering the price of each roll for a consumer.

Addressing market exposure from the perspective of the consumer

Consumers who invest in a free-to-play game that has a chance sale also known as a gacha system are subjected to these conditions to spend their disposable income. These conditions mainly pertain to quantity sold and desired quality of an idea sold, but leave out the last facet of exposure time for the product to be sold. In short, the current system only has quantity and quality but mostly lacks the time component. Specifically, the next question to ask is how long must a consumer be exposed to the desired product in order for the consumer to buy the desired product?

When this gacha system is applied on a large scale to the general populace, the market capture radius for a gacha game is large due to the almost infinite quantity of copies supplied to the consumer ecosystem. The free barrier to entry drives down the price of other games that have similar elements in their games as the one presented in the gacha game. Since there is a large quantity of copies of the free-to-play video game made by a video game company which is easily accessible to any consumer and is made as generic as possible to satisfy almost all of the targeted consumer market, the last dimension that a gacha game will want to compete in is time. In the time dimension, there are two important factors that consumers will follow.

First, disposable income regenerates over time for consumers. Consumers may receive monthly or weekly pay checks from work or other sources. This means that gacha games or games with chance systems are incentivized to release buyable content that appears every month depending on the income level of the consumer base.

Second, consumers are primarily focused on one game at a given time (except when a person is playing and multitasking with several devices at once). This means that consumers will likely switch to another game if they choose to do so. To minimize the chance of disposable income from going to other sources, the game owner will want the consumer to be exposed to the gacha game as long as possible. Therefore, games that are engineered to take more time such as randomization systems in their gameplay are an ideal choice to keep the consumer only playing the target game and not other games.

Overall, there is another reason for game owners to select these game design choices like using a randomization system to lower the chances of a consumer being exposed to another game and giving money to the other game. Keeping the consumer engaged with the gacha game will increase the time window for a chance that the consumer will pay for purchasable content in the game. The longer a consumer spends in a game, the more opportunities per unit of time that a reason, a thought to buy digital content, and a random whim will occur. This follows the logic that keeping a consumer in a store, IKEA, casino, or supermarket will expose the consumer to chances or opportunities to buy a product in the time dimension. If it takes 10 seconds to buy a product, giving a consumer 20 seconds to buy a product may raise the chance that a consumer will buy two products by raising the rate of a fixed 0% of buying a product to an equal to or greater than 0% chance of a second product being sold without knowing the intentions of the consumer.

Using this logic, if it takes 5 seconds for a consumer to roll for a product, then having more rolls would keep the consumer longer in the game. If a consumer has 100 rolls then they would take 500 seconds in the game which is longer than 1 roll that makes the player only stay 5 seconds in the game. Therefore, lowering the price of each roll so the consumer will roll more will keep the player longer in the game. This can be said as an additional benefit for the game companies that want consumers to spend in the free-to-play game. In short, a free-to-play video game is a storefront where a consumer being in the store will extend the likelihood that this consumer will spend something if this consumer remains in the store. This can be in the form of buying more rolls, items, and currency in the game.

Therefore, the game owner would be incentivized to keep a consumer focused on the gacha game to prevent a consumer from going to spend in a different game and to keep a consumer in the game as long as possible to increase the chance of the consumer buying a product within the gacha game. These two sub-incentives drive the second factor and complement the first factor for game owners to be involved in the time dimension.

Consumers and their source of disposable income

When talking about consumers, it is important to address and define the amount of power or disposable income that they can spend in the free-to-play video game. Consumers are also affected by things that may reduce their disposable income or limit their spending ability.

The effects of having a gacha game or game using a chance system is limited by the amount of disposable income and the type of hardware the game is limited towards. The secondary or nonessential economy is in direct competition to and is supported by the primary or essential economy. Consumers will need to pay for food, electricity, taxes, and other necessities. Observing the consumer price index or purchasing power parity, regional utility prices, and cost of living index would be ideal to estimate how much are consumers spending on the primary economy. Consumers will also need to make money which is from a job or employment. This can be considered as a part of real wages. Further observing the average income or average real wages for consumers in a region minus the spending or average spending in the primary economy can result in an estimate on how much to price a digital product. Overall, income must be subtracted from primary economy costs. What money is left over is considered disposable income.

The second limitation is the type of hardware the consumer needs to use to play the game. A game that requires a common mobile phone has a low capital cost for a consumer to use to play the game. However, a game that requires an expensive console to play may make the game have less reach. This can also be said about software sizes. High end games that require large software sizes may not fit or run optimally on a common mobile phone in comparison to a costly but spacious console system. Furthermore, games that use servers can be played at high graphic settings will still be bottlenecked by systems or devices that can only run lower graphic settings which the consumer has to use to play the game. Overall, this limitation depends on the consumer to have the right type of hardware.

As games become more expensive to run and if disposable income diminishes, less customers will be able to afford or access the game. This implies that the supply and demand curve of a consumer willing to purchase a game is limited to the amount of purchased and runnable devices for a game. Although, people that may not have the device can still purchase the game as a gift or for collection purposes. However, these people do not have access to the game which disallows any chance or fixed priced systems to be used on these people. Therefore, the market only applies to a consumer when the game is running and is being used by a consumer on an accessible device.

This chart shows that there is a limit in the quantity of video game copies that can be sold based on the amount of consumers that have a device which can play the free-to-play game. This gaming device limit is the maximum amount of devices used by consumers in the gaming market. This is based on the consumer using a single copy of the game at a time.

Although consumers may hold multiple devices and copies of the game, the amount of money that they are willing to spend per copy can be added up to the total amount of money that the consumer is willing to spend on an idea or product. A person could spend 40 rolls for a chance system across 2 game devices, with 20 rolls per each device. This person can still be classified under 40 rolls for an idea in a desired product. In short, each consumer will likely at least have 1 device because of the perception that a person mainly plays 1 game at a time with some exceptions.

Summary

Overall, free-to-play video game companies have a choice between selling a digital product at a fixed price or by selling individual chances of getting the digital product to consumers. Consumers are split between whales, minnows, and free-riders. Whales are people who have saved a lot of money and will spend on what they like regardless of price differences. Minnows or low spenders may not have a lot of money and will go for the cheaper option out of what they like. Free-riders are people who don't spend any money in the game. A game company selling at a fixed price is inefficient because there are consumers who can’t spend more on the product and consumers that can’t afford the product. Selling individual chances to consumers is more effective because chances can be made to be affordable for all consumers and people who really want the product can buy more chances to spend all of their disposable income. Game companies are incentivised to price each chance as low as possible to make it affordable for all consumers, to make more rolls to control probability by the law of large numbers, and to make more rolls to increase the time window of a consumer who will possibly spend something by only playing the free-to-play game. The cost or value of the digital product should be equal to the consumer with the highest disposable income. Consumers can regenerate their disposable income, usually play one game at a time, are usually focused on a single video game device at a time, have disposable income reduced by living costs, and are restrained by hardware costs to play the game.

In the next article, I will test these concepts in a simulation by making a group of consumers that have varying levels of disposable income to buy a product in a free-to-play game at a fixed price and at a variable price which is how many chances can each consumer afford with their disposable income.

Patreon to support the website: patreon.com/ReiCaldombra As a free member you can get notified about new uploads on Blog Under a Log. You can also become a paid member to financially support the website, but any support is greatly appreciated!

First Part: Economic Analysis on Gacha Game Pricing - Part 1 - General History — Blog Under a Log