Economic Analysis on Gacha Game Pricing - Part 5 - Consumption and Sustainability

Written by Researcher Alex and Edited by Rei Caldombra 12/15/25 Previous Part: Economic Analysis on Gacha Game Pricing - Part 4 - Simulating Consumer Spending — Blog Under a Log

Video game companies usually must cater to consumers with different levels of disposable income. In free-to-play gacha games, video game companies want consumers to spend their money on rolls / pulls for in game products. Consumers will spend their money towards what they like in their imagination to the digital product offered in the free-to-play game. These consumers can leave to another video game which has the desired digital product that aligns with what the consumer likes in their imagination. Companies that run free-to-play games will encounter four types of consumers: financially risky consumers, not financially risky consumers or middle wealth consumers, wealthy consumers, and free-to-play consumers.

Free-to-play consumers will play the game but not spend any money in the free-to-play game. They use up resources dedicated for running the free-to-play game.

Financially risky consumers are consumers that can spend money frugally, with their budget being equal to the price of one roll or slightly higher. The key criteria is at any specific point in time that the price of one roll rises or if the consumer’s disposable income drops, the consumer cannot afford to buy a roll immediately right after this specific point in time. This would be the definition of a financially risky consumer.

Middle consumers also known as not financially risky consumers are consumers that can still afford to buy a roll after the price of one roll rises or if the consumer’s disposable income drops. However, they can only afford up to 1 instance of a digital product. The key criteria is at any specific point in time that the price of one roll rises or if the consumer’s disposable income drops, the consumer can still afford to buy a roll immediately right after this specific point in time.

Wealthy consumers are consumers that can still afford all the rolls required for a digital product. This type of consumer is the same as a not financially risky consumer while being able to afford more than 1 instance of a digital product. They can go to different free-to-play games and roll for other similar desired digital products after getting their first desired digital product in a free-to-play game.

A company using a free-to-play model to gather both financially risky, middle, and wealthy consumers has a primary goal of catching consumers that are financially stable which are logically middle and wealthy consumers. Over time, financially risky consumers will likely be phased out by being unable to support the purchases of chances for the digital product or new digital products. This will cause the company to listen to middle and wealthy consumers more over time. If the company caters to the middle and wealthy consumers while neglecting the financially risky consumers, the financially risky consumers will leave the consumer group, which may result in losses in player count and spending power. However, the player count will stabilize with a core audience being the middle and wealthy consumers.

The division between the financially risky consumer base vs the middle and wealthy consumers can create a wealth divide. If multiple free-to-play model games shed financially risky consumers, then these finllancially risky consumers will create a trend system where these consumers shift between free-to-play games. This may take the form of a hype wave or sporadic nomadic wanderings. In this notion, these people may shift to free platforms if they cannot play the games they don’t want or can’t afford but still like to watch it in the form of content such as videos and streaming. In short, a group of people who want a desired digital product that either like or can access free-to-play games will hop between free-to-play games looking for a digital product that aligns with what the consumer imagines and likes.

Streaming or video platforms may take these people out of the free-to-play game ecosystem by turning these people into viewers. Viewers will have little to no agency compared to being able to play a game. Using this logic, a downturn in the free-to-play ecosystem may be identified when there is an increase in viewers on video platforms and a decrease in financially risky consumers in games. In short, more people who are unlikely to spend money will be watching the game rather than playing the game. This also shows that video platforms are in direct competition with free-to-play games to specifically attract an increase in their active player base. This may indicate that games such as free-to-play games may face difficulties when trying to attract new players to specifically increase the player count of a game.

In this sense, video platforms and free-to-play games that do not provide any form of agency to a financially risky consumer have equal weight. Since video platforms have no or minimal agency such as a subscribe or like function, video platforms must have the exact content that consumers want. Therefore, video platforms must produce content about the free-to-play game that the financially risky consumer likes, which a higher quantity of content is created to fit the preferences of every financially risky consumer. On the other hand, free-to-play games can attempt a quality approach by catering to the financially risky consumer base. This may waste resources by catering to the financially risky consumer base but this provides an edge over the nearly fixed amount of agency a video platform provides. This would logically attract financially risky consumers that want to play to their preferences and agency back into the consumer group of the free-to-play game. Although, this effort may be counterintuitive for free-to-play games to accomplish from a financial risk perspective.

The Role of Video Platform Content Creators

Interestingly, content creators for video platforms who can influence the game are a category that fits the middle and wealthy consumer group if the financially risky consumer group has left the free-to-play game. Indirectly, content creators for video platforms are providing a substitute in the form of a preferred video for financially risky consumers to return to the game. Why return to play a game when a content creator for a video platform already provides or creates your preferred content of the free-to-play game? Based on this logic, this means that content creators for video platforms who are in either the middle or wealthy consumer group are creating a substitute good economic barrier against and intended for financially risky people to join the free-to-play game. This may be a possible barrier to entry for a free-to-play game to specifically increase player count for the free-to-play game through financially risky consumers.

However, there is the possibility that a financially risky consumer or any type of consumer may watch and play the free-to-play game at the same time or alternate. A common example of this may be for watching a tutorial while completing the same section in the game as the tutorial, getting different story possibilities, or watching a cutscene of the game and then wanting to play to the part of the same cutscene, playing a section for a score and the watching videos of other players on their scores. In this sense, consumers are aligned with the content of the game. This is when consumers without attachment to financial incentives have a desire to play the game. This is when the free-to-play game becomes a complement instead of a substitute to a video platform with the aligned content. In short, the content that the company provides in the free-to-play game aligns with the consumers which is a key distinction to when the consumer is not aligned to the content that the company provides in the free-to-play game. This unalignment would occur if the company caters to the middle and wealthy consumers and not the financially risky consumers. This would also occur if the financially risky consumers are satisfied but the middle and wealthy consumers are discontent which would not be financially optimal to the company. Only catering to any one of the consumer groups while leaving out the other two groups would not be financially optimal. Two other extreme possibilities are if all three of the consumer types are satisfied which would likely cause the free-to-play game to reach the maximum player count or none of the consumer types are satisfied which would draw all players away from the free-to-play game.

Irrationally Dedicated Consumers and Stubbornly Irrational Consumers

Regardless of the type of consumer, certain consumers may just want to play the game regardless of financial implications or substitutions like video platforms. Other audiences may only want to watch the game rather than play the game regardless of any incentives. Other audiences may only want to play both games separately or at the same time. This audience must be considered to account for irrational demand which overrides logical reasons for switching or dual use between the free-to-play game and watching the free-to-play game on a video platform. These audience groups are logically immovable and form the base of any consumer type as a fixed population. This is in contrast to consumers who are willing to move between free-to-play games and content on a video platform. For instance, a wealthy consumer may only watch a game while spending money on supporting the free-to-play game albeit through different means like merchandise. A financially risky consumer may only play the game while not spending a single dollar on the free-to-play game. Or a middle consumer with medium wealth will play the game and watch the game only at the same time while only spending moderately.

In this context, free-to-play games and video platforms have little to no control over these players and should rather focus on consumers that can be influenced by aligned content and consumers that can be moved between video games and video platforms.

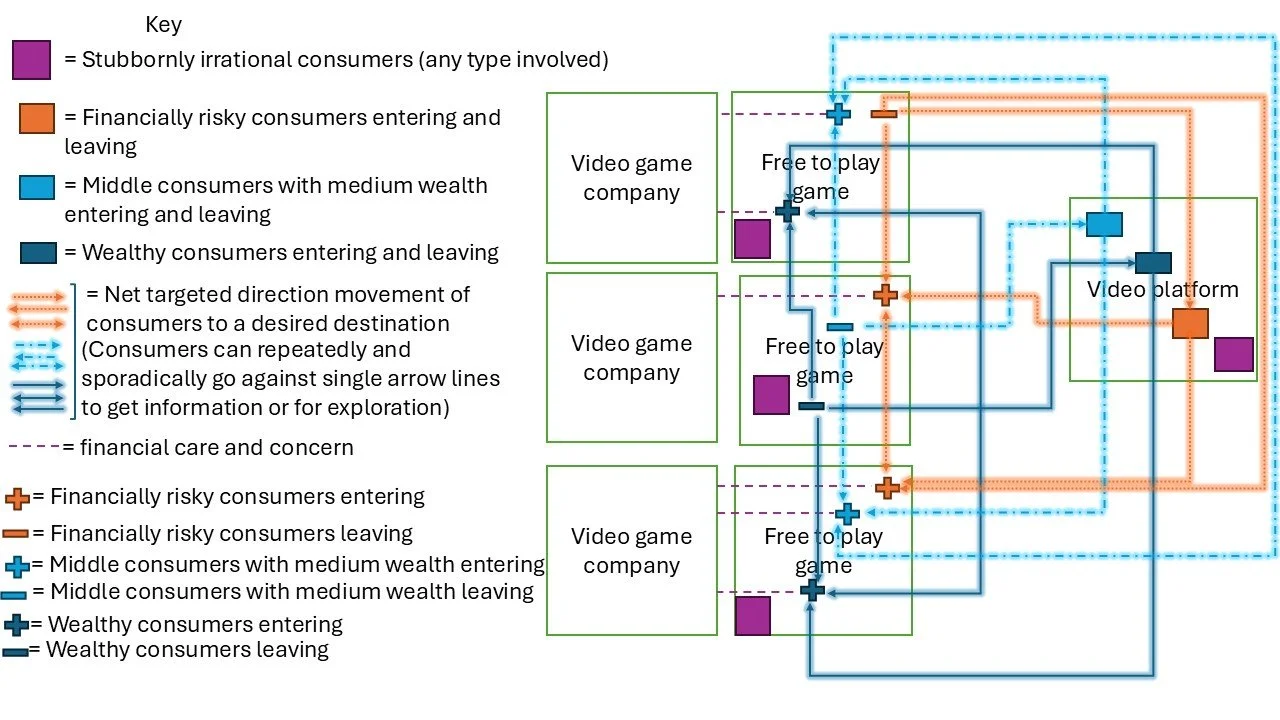

Creating a Sample Free-to-play Game Consumer Ecosystem

Using the logic presented in determining consumer types, I will create a diagram where consumers move around between a video platform and several free-to-play games. In each of these free-to-play games, a video game company will prioritize a unique combination of consumer types in this diagram.

This diagram demonstrates how the flow of economic consumers are dependent on the video game company that is catering to specific consumer types. Consumers are free to switch between free-to-play games to find their favorite content and a video platform to find their own favorite content. Even if consumers are focused on one free-to-play game, they can also explore other free-to-play games and return to their originally focused game or even go to a video platform to watch other free-to-play games or informative tutorials and then return to their originally focused game. Certain consumers may be incentivized to switch between free-to-play games which may reduce the net movement of consumers to zero by moving both ways between games which can be represented by lines with double pointed arrows in the diagram towards two free-to-play games or to a free-to-play game and to a video platform. These free-to-play games may have equal weight to specific consumers in having their desired content like digital products being identical in value within these free-to-play games. This represents the concept of an economic substitute within this diagram as double pointed arrows. Furthermore, the diagram contains irrational consumers who stick to a single free-to-play game or a video platform. These are addressed as consumers who are stubborn or won’t move to a different game or to a video platform from playing the video game.

This diagram visualizes how video game companies anchor audiences in a free-to-play game market by using resources such as time or money to cater to a specific audience. Not catering to a specific audience will cause the specified audience to move to either a different free-to-play game or a video platform. In relation to consumers being unable to pay for a single roll to get their desired product, consumers may shift to other free-to-play games that offer a substitute of their desired product or if there are no visibly desirable product that is affordable to the disgruntled consumer. In that scenario, the disgruntled consumer will shift to a video platform if they are not an irrational consumer. This type of consumer will wait until a game offers their desired product at an affordable price and shift to the game that has the desired product.

The Bank and Store Analogy

Based on this logic, consumers may be given the opportunity to save money when they are only on the video platform because they are not spending any money on any free-to-play game. In this sense, a video platform similarly operates like a bank for consumers while a free-to-play game is a store where the consumer can spend money on their digital product. However, the bank effect may not last long if consumers rapidly shift between games and a video platform with savings have not been given time to grow which may hinder consumers spending at larger price points because consumers will constantly get money and instantly spend their money. This places consumers into a semi nonpaying and financially risky state which prevents the growth of consumers to a wealthy state.

This bank effect will also not work if a consumer exhausts all of their money and shifts between free-to-play games because the consumer does not have a break in spending by not going to the video platform to save money. However, consumers that are wealthy can go between multiple free-to-play games to spend money without necessarily going to the video platform to save money. Yet this method may drain middle and wealthy consumers quickly if they cannot sustain this type of constant spending which may place them into a semi nonpaying and financially risky state.

Having options for consumers to shift between free-to-play games instantly may not be suitable for growing wealthy consumers to spend in these free-to-play games. A gacha free-to-play game should avoid similar content seen in other gacha free-to-play games that a consumer may also like. In short, digital products or favored content should be unique to a single free-to-play game to prevent wealthy consumers from overheating to spend money on other free-to-play games that have identical digital products.

Low Prices of Rolls Reduce the Growth of a Wealthy Consumer Group Type

Setting a lower price per roll (also known as a price per chance) will likely shorten the time in which consumers need to save money for rolling which increases spending frequency per time interval but prevents a consumer from spending at higher price points like a middle or wealthy consumer.

If combined with a rapidly switching consumer, then this may decrease the chance that the consumer can become a higher paying consumer. Conversely, if price points are higher, this prevents financially risky consumers from paying instantly but gives consumers the option to move to a similar game or a video platform. However, game companies are not incentivized to individually raise their price per chance if there are substitute games with substitute digital products in the market because they will lose these financially risky but still spending consumers to these substitute games with substitute digital products and the video platform.

This shows that games with low spending per chance prices that cannot go any lower are at risk of middle and wealthy consumers becoming financially risky consumers or consumers that do not have money left and must save up to pay for a chance to get their digital product when there are substitute digital products in other games.

Overheating Consumers in a Disposable Income Desert

This presents a problem where free-to-play market ecosystems are weak against general economic trends. An increase in financially risky consumers subjected to rapid overheating by an increased chance of moving between several free-to-play games with substitute digital products at low price points creates a hostile environment for consumers to grow their money by waiting in a video platform. However, if disposable income does not replenish for the consumers over time, the net disposable income per consumer remains at 0 dollars, or the growth rate is lower than the free-to-play spending rate, then recovering the free-to-play economy may be impossible at that point. Waiting for an increase in overall consumer disposable income may be a viable option. Companies may be incentivized to either gather as much disposable income as possible or to manage a slow drain of middle and wealthy consumers to hold out until overall consumer disposable income increases.

Oasis in the Desert: A City of Golden Gacha Games

However, the effect may be lessened if the digital product in the game is unique which caters to a specific consumer group. This consumer group only goes between the free-to-play game that has the unique digital product and a video platform. Since there are no other free-to-play games with substitute digital products, the consumer ecosystem cannot be subjected to overheating or having consumers rapidly move between other free-to-play games with substitute digital products. This gives no consequence to the free-to-play game with the unique product to raise price per chance. Therefore, raising the price per chance forces out financially risky consumers to the video platform, allowing them to gain money to the level of a middle or wealthy consumer while current middle and wealthy consumers pay for the high price per chance and can either spend more or replenish their disposable income. Ideally, wealthy consumers are the only ones that can spend until they are middle consumers with medium wealth to replenish quickly. Financially risky consumers can save until they are wealthy consumers and then join this wealthy consumer group cycle. Although, all consumers should have a stream of replenishable disposable income or the entire consumer ecosystem may collapse. This logic to raise price per chance to create an ideal sustainable free-to-play market is contrary to the advice of lowering price per chance to gather as much spending as possible from consumers. The ideal scenario is isolated by a unique digital product while the other advised scenario is surrounded by substitute digital products.

To create an ideal scenario with multiple identical substitute digital products, grouping several free-to-play games with substitute digital products under a single video game company would be an ideal solution to eliminate the competition between getting disposable income by individual video game studios. As long as the digital product substitutes within a group of free-to-play video games are not substitutes to an outside video game digital product, then consumers would be contained within that video game group with a unique whole digital product. The free-to-play video games in the group can all simultaneously raise their price per chance without fear of competition. Consumers who like that digital product will go to the video platform and save money while wealthy consumers across the free-to-play games will spend money on an expensive price per chance. Financially risky consumers cannot overheat due to being unable to spend money instantly on a chance and will not leave the market because there are no digital product substitutes in free-to-play games outside of the free-to-play game group. As long as disposable income replenishes for all consumers, then this is a possible solution for making a sustainable free-to-play game ecosystem.

In short, a company or a video game company should control a bunch of free-to-play games together to control the prices towards a unique product that is in all of these games. This monopolistic behavior is needed to prevent competition from other free-to-play games run by other video game companies that have similar digital products. This competition is harmful because it forces the price of each roll to be at a minimum price, thus preventing the option of raising the price of a roll when the company desires to raise the price for reasons like letting consumers regain disposable income over time.

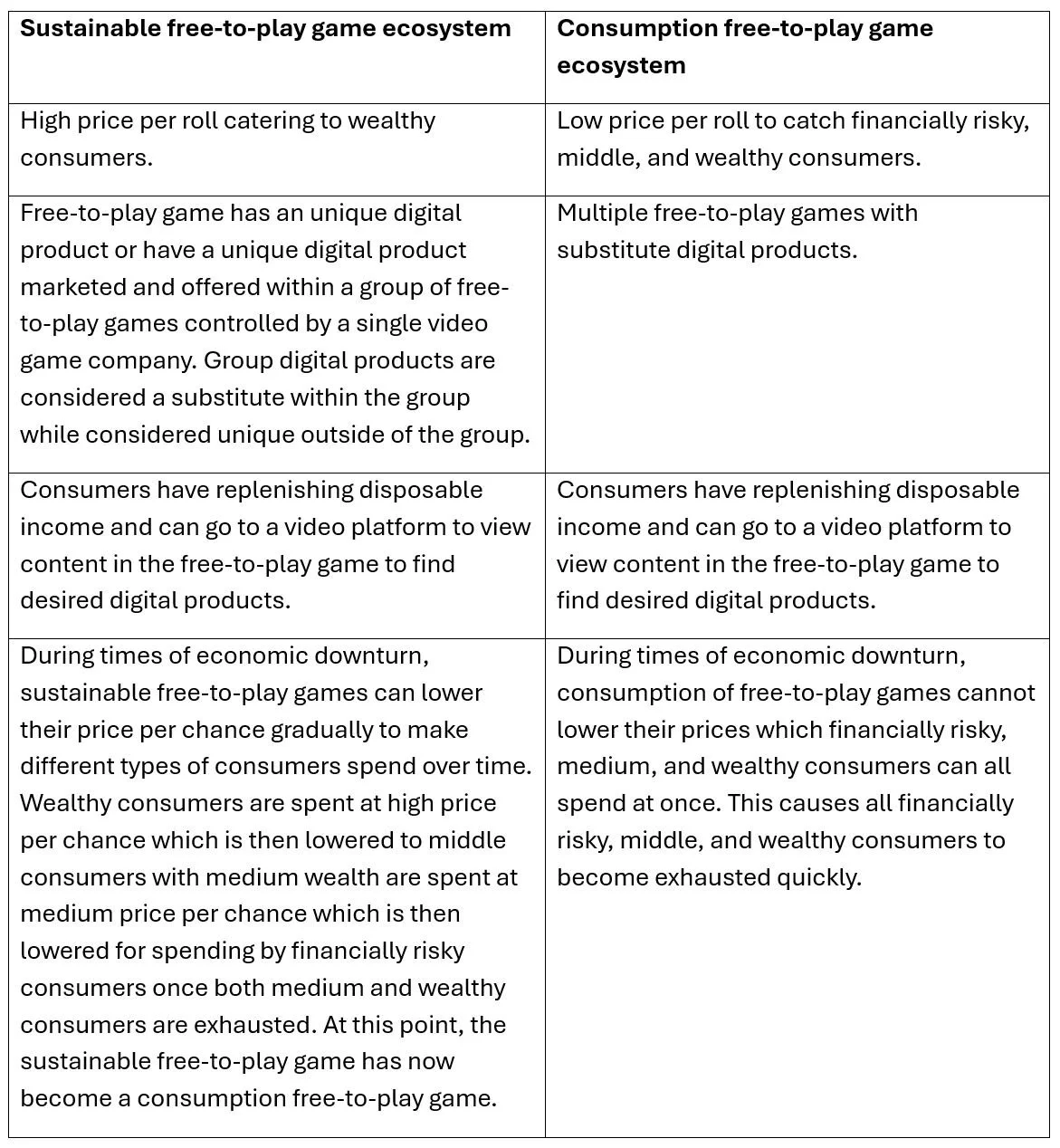

Two Strategies for Free-to-play Games to Survive Economic Problems

There are two strategies for free-to-play games to retain consumers to spend in a free-to-play game. The first strategy is to use a high price per roll to allow financially risky consumers to accumulate disposable income to become not financially risky consumers. This is a “Sustainable free-to-play game ecosystem.” The second strategy is to set a low price per roll. This causes all consumers that have money to spend for rolls at an affordable price towards a desired digital product which will drain all consumers of disposable income. This is called a “Consumption free-to-play game ecosystem.” Overall, I have provided a table below to show the qualities of each strategy.

This table shows that there are two types of gacha free-to-play game ecosystems. There is a sustainable ecosystem that tries to keep and convert an entire player base to become wealthy consumers to support the free-to-play game. There is a consumption ecosystem that tries to extract as much disposable income out of financially risky, middle, and wealthy consumers. In the overall gacha game economy, if there are more sustainable ecosystems than consumption ecosystems, then the industry as a whole would last longer during economic downturn with more sustainable ecosystems with wealthy consumers first being expended and then middle consumers and then financially risky consumers can be allowed to spend by lowering the price per roll over time. This is in comparison to consumption ecosystems with low price points where financially risky, middle, and wealthy consumers can all spend at the same time. In short, sustainable ecosystems can control their consumers to spend over time until these sustainable ecosystems become consumption ecosystems with low-cost price per chance. On the other hand, if there are more consumption ecosystems than sustainable ecosystems in the gacha game economy, then there would be a rapid reduction of consumption of free-to-play games which would only leave sustainable ecosystems left in the gacha game economy.

Summary

The macroeconomic situation of free-to-play games is dependent on if consumers have disposable income to spend and are willing to spend towards a digital product that aligns with what the consumer likes in their imagination. Consumers need time to regain disposable income in order to not become financially risky consumers. However, low prices per roll and market competition contribute to consumers overheating by draining their disposable income through affordable pricing. To solve this problem, free-to-play companies need to raise prices through monopolistic practices to allow consumers to grow their disposable income. Gacha companies that can raise prices to a dedicated consumer base can last longer by slowly draining their consumers of disposable income in comparison to other gacha games that use low prices to quickly drain all of their consumers of disposable income. This may generally explain why large game companies survive by having several gacha games in their company portfolios during times when consumers do not have enough disposable income to spend towards gacha games.

Patreon to support the website: patreon.com/ReiCaldombra As a free member you can get notified about new uploads on Blog Under a Log. You can also become a paid member to financially support the website, but any support is greatly appreciated!

First Part: Economic Analysis on Gacha Game Pricing - Part 1 - General History — Blog Under a Log